Systems planning in a crisis

Summer is when schools plan for the coming year. A process that is intense even in the best of times is further complicated by COVID-19. The pandemic presents schools with particular challenges around health and safety and around preparing for in-person learning, remote learning or a combination of both. All of these challenges, of course, are compounded by the equity challenges with which most schools are all too familiar.

Crisis planning is surely upon us. While schools need to be responsive to the immediate crisis, they also need to think about long-term, sustainable models of effective education. Crisis planning is unavoidable. But it needn’t force schools to abandon systems planning.

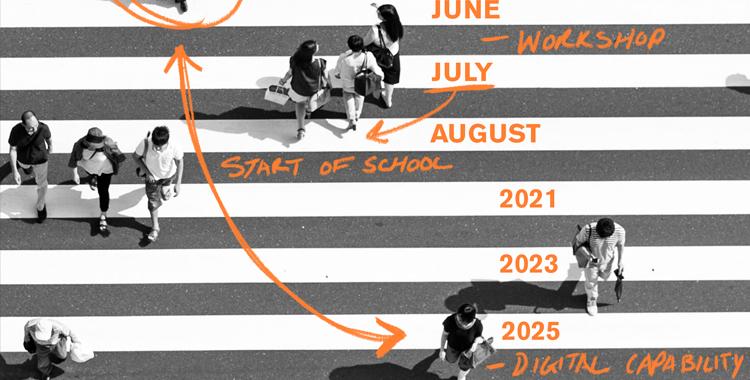

For three years, we at ASU’s Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College have been working with partner districts to design and field Next Education Workforce models that seek to 1) provide all students with deeper and personalized learning by building teams of educators with distributed expertise and 2) empower educators by developing new opportunities for role-based specialization and advancement.

In mid-June, we’re running a weeklong workshop (online of course) with our partner districts and schools to prepare for the 2020-21 school year, during which we expect to have more than 700 ASU teacher candidates working as residents in schools. Superintendents, principals, teachers, and our own faculty will address how schools can best configure teams of educators to serve students.

Some of these models will include teacher candidates. Other teams may consist only of in-service certified teachers. Still others may incorporate community educators whose expertise and skills can benefit learners. Many will also incorporate technology as we fold remote learning modalities into our team-based models.

We’re not starting from scratch. For three years, we’ve been working with districts to develop Next Education Workforce models. As a college of education that excels at teacher preparation, we started with our bread and butter, working with 11 schools in two districts to pilot a team-based residency model in 2018-19. We’ve published a white paper, based on research supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, that describes the pilot and shares insights about what succeeded and where we need to deepen our work. We’ve also written a series of implementation briefs that address specific educator roles, financial considerations and district readiness.

Readers of this blog who have seen me make the theoretical case for the Next Education Workforce can now read about what it looked like in practice, when applied to teacher prep, and about what teacher candidates, teachers, principals and superintendents have to say about the experience.

In the 2019-20 academic year, we expanded our team-based residency model to 14 districts. For 2020-21, we will expand still further, reaching more districts and developing team-based models that are not limited to teacher-prep residencies.

To support schools in developing Next Education Workforce Models, we are publishing a set of resources that explain why these models matter and, crucially, what practical operational steps can be taken to implement them. Included in this work are spotlights on partner schools that have results and experiences to report.

We’re looking forward to our June workshop. So much of what is urgent to address in the time of COVID-19 is also structurally important to address for the long term.

Take, for example, teacher shortages, one of the problems that our two pilot districts sought to address through team-based residencies in teacher-prep. COVID-19 is likely to accelerate teacher retirements and cause long-term absences.

It is also likely to accelerate the pace at which schools have to integrate technology and remote learning. At times, it is likely that some or all learners will be remote. Sometimes the instructors or content experts will be remote. At other times, perhaps, everybody will be somewhere other than school. But learning has to happen. The innovations in remote learning and instruction that we develop during the pandemic will have long-term benefits for how we bring expertise into rural schools and other communities that aren’t fully staffed with the pedagogical and content expertise their learners need.

And, of course, the need for wraparound services such as socio-emotional support, counseling, healthcare, transportation and more will likely be more urgent as learning continues during the pandemic.

All of these issues have been made worse by COVID-19. However, they are all-pre-existing conditions of our education system that will still be with us once the pandemic passes.

At first, it might seem quixotic to forge ahead with the Next Education Workforce and all the big structural change it demands at a time when schools have so many immediate, crisis-induced decisions to make.

But what we and our partners are finding is that many of the school-related challenges presented by COVID-19 are not new. Rather, they are acute manifestations of the challenges that Next Education Workforce models seek to address.