Facing the Climate Change Catastrophe: Continuing an Urgent Conversation

This blog was written by Hikaru Komatsu and Jeremy Rappleye (Kyoto University Graduate School of Education), and Iveta Silova (Arizona State University Center for Advanced Studies in Global Education) in response to the recent blog by Edward Vickers about the role of education in climate change. It responds to Professor Vickers’ critique and expands on the discussion paper presented by Professors Komatsu and Rappleye at the ASU Symposium on Global Learning Metrics in November 2018.

We welcome Edward Vickers’ response to our blog “Facing the Climate Change Catastrophe: Education as Solution or Cause?”. We see it as beginning of a much-needed discussion about whether dominant forms of conceptualizing education – ones rooted in the ‘modernist Western paradigm’ (Sterling et al., 2018) –are in fact a solution or a cause of the trouble we now face. While Vickers (2018) may have misread our initial intervention as “anti-western”, arguing that “blaming Western modernity is not the answer”, our intent was not blame. Instead, we believe that gaining some critical distance from Western modes of thinking and education –a particular cultural arrangement, not a universal phenomenon – is a crucial step for locating alternatives as we face the climate change catastrophe. We believe that it is more urgent than ever to reimagine education on a much wider scale and a far deeper level, considering alternatives beyond the Western horizon that can contribute to our collective efforts to think in new ways.Although we may not agree on particular strategies of addressing climate change, we are grateful for the chance Vickers’ response provides to continue this urgent conversation.

Anticipating that our forthcoming article in the journal ‘Anthropocene’ will provide a more thorough response as compared with the limitations of blog space, here we would like to simply clarify a few issues surrounding the data utilized by Professor Vickers. We appreciate that he included data of Ecological Footprint (EF) to assess the environmental impacts of different countries. The primary reason is that, as many readers will already know, EF is a more comprehensive parameter for environmental impacts than CO2 emissions: EF considers not only emissions of waste including CO2 but consumption of various materials. That said, we did find two issues with Vickers’ analysis. First, he did not clarify that there are two different types of EF or that the one utilized in his response does not seem relevant to the argument he is making. Second, he seems to have selected data for particular countries that directly support his conclusions, rather than look at the wider global picture.

Concerning the first point, EF is defined in two different ways. These two EFs are called EF of Production and EF of Consumption. EF of Production for a given country is calculated based on production of the country, while EF of Consumption is based on its consumption. If Country A establishes factories in Country B to produce industrial products and then imports the products back home, the EF of Production locates the environmental impacts of this production in EF for Country B (i.e., where the factories are located). In contrast, the EF of Consumption registers the environmental impacts of this for Country A where consumption takes place (i.e., where the demand for those products is and where they are consumed). Professor Vickers used EF of Production in his analysis, but we feel he should have used the EF of Consumption: one important issue to be clear on is how certain countries ‘export’ their environmental footprint abroad and thus obscure who is ultimately responsible. Here is one recent article focusing on China and the United States that illustrates some of the complex, troubling, and dirty issues involved.

Concerning the second point, Vickers appears to have selected countries with relatively low EF among the Western countries (e.g., Norway, not the United States) and those having relatively high EF among non-Western countries (e.g., South Korea, not Costa Rica). Note that EF of Consumption was 5.76 Earths for Norway, 8.59 Earths for the United States, 5.85 Earths for South Korea, and 2.48 Earths for Costa Rica. The issues he raises here are important to nuance – we agree – but we also think it is important to survey the situation more expansively beyond simple country-to-country comparisons.

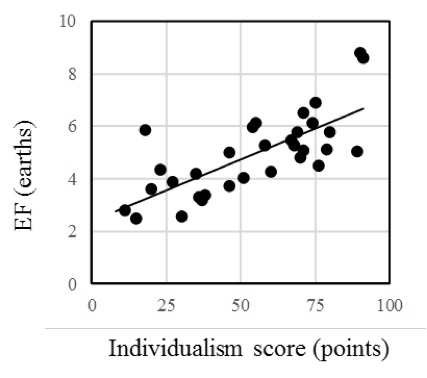

So what happens when we utilize EF of Consumption instead of EF of Production and utilize data for all relevant countries? We defined the ‘relevant countries’ to be those with a sufficiently high life expectancy to eliminate potential arguments about the trade-offs between long, fulfilling lives and environmental sustainability. The variation in the degree of individualism among countries assessed by Hofstede cultural dataset explains 54% of the variation in EF of Consumption (Figure 1, Komatsu, Rappleye, & Silova, forthcoming). This strong relationship, as well as the fact that countries with such high degrees of individualism are observed primarily in Western Europe and North America (see Figure 4 of Komatsu & Rappleye, 2018), suggests the need to take seriously a working hypothesis –one among many, of course –that the Western historical-cultural-institutional-economic matrix potentially contains elements which may be environmentally detrimental. Moreover, to the degree to which ‘subjectivity’(i.e., self-construal) is linked to environment, it opens space for education scholars to work and think, rather than assuming that ‘education has nothing to with the environment’or simply rolling out narrow Education for Sustainable Development (ESD)-style curricular add-ons. This is a key issue moving forward: older analytical/theoretical models developed at a time when the environment was not an issue may end up hindering rather than helping our efforts to address the climate change catastrophe.

Figure 1.Relationship between individualism scores and Ecological Footprint (EF) of Consumption (Komatsu et al., Forthcoming). A high individualism score indicates a higher level of individualism. The unit of EF is “the number of Earths demanded” assuming that the entire world population consumes in the same way as the average person for a given country. Individual scores and EF of Consumption were derived from Hofstede et al. (2010) and the Global Footprint Network (2017).

On this point, we do feel that Professor Vickers’ suggestion that our work is somehow a resuscitation of “oriental wisdom” arguments is unfair and illustrative. The distinction between ‘independent’and ‘interdependent’ self-construal that he seems to read as a mere refurbishing of Orientalism/Occidentalism tropes is, in fact, derived from several paradigmatic studies in the field of psychology. The major paper by Markus and Kitayama (1991) is one of the most widely cited papers across the entire social sciences over the past several decades, and is backed by rigorous empirical research (e.g., Heine & Ruby, 2010). Their more recent paper (Markus & Kitayama, 2010) discusses the mutually constituting relationship between cultures and selves. These pieces underscore that culture cannot be reduced to simply ideological control mechanisms by political elites, as it is now so often portrayed within Anglo-American scholarship. Unfortunately, the insights provided by the Markus and Kitayama studies have not been widely discussed among education scholars, perhaps –at least in part –because the field continues to prefer the older analytical/theoretical model of the universal ‘human’, and views attempts to discuss different, culturally-mediated human experiences as a divisive move rather than something that opens up new imaginative horizons. Our point, of course, is not that the ‘East’ has the answers, but instead that recognizing difference allows us to gain the critical distance necessary for reimagining.

We hope that our response does not shut down but instead further stimulates dialogue among scholars, practitioners, and policymakers (on that note, see the emerging conversation around these issues generated by a recent symposium at Arizona State University). In closing, we appreciate Vickers’ willingness to engage and his effort to respond to our blog article. This sort of conversation is precisely what we need: a continuing exchange is more important than finding the ‘right’ answer. An open conversation can help us understand the issues more deeply and collectively formulate some workable ‘solutions’ to the difficult questionsposed to education by the climate change catastrophe. Thinking pragmatically is crucial in these perilous times. More to come from us, but we hope others will respond as well. Sincere thanks, Ed!

The authors can be reached at the following email addresses: Hikaru Komatsu ([email protected]), Jeremy Rappleye ([email protected]), and Iveta Silova ([email protected]).

References

Global Footprint Network, 2017. Public data package 2017. http://www.footprintnetwork.org/licenses/public-data-package-free-edition-copy/.

Heine, S.J., Ruby, M.B., 2010. Cultural psychology. WIREs Cognitive Science1, 254–266. doi: 10.1002/wcs.7.

Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G.J., Minkov, M., 2010. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind (3rd Edition). McGrow Hill, New York.

Komatsu, H., Rappleye, J., 2018. Will SDG4 achieve environmental sustainability? Center for Advanced Studies in Global Education (CASGE) Working Paper #4. https://education.asu.edu/sites/default/files/working_paper_4_final.pdf.

Komatsu, H., Rappleye, J., Silova, I., Forthcoming. Culture and the Independent Self: Obstacles to Environmental Sustainability? Anthropocene.

Markus, H.R., Kitayama, S., 1991. Culture and the self: implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review98, 224–253. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.98.2.224.

Markus, H.R., Kitayama, S., 2010. Cultures and selves: A cycle of mutual constitution. Perspectives in Psychological Science5, 420–430. doi: 10.1177/1745691610375557.

Sterling, S., Dawson, J., Warwick, P., 2018. Transforming sustainability education at the creative edge of the mainstream: A case study of Schumacher College. Journal of Transformative Education 16 (4), 323-343.